Thursday, April 9, 2015

The Difference Between Being Really Smart ... And Being A Genius

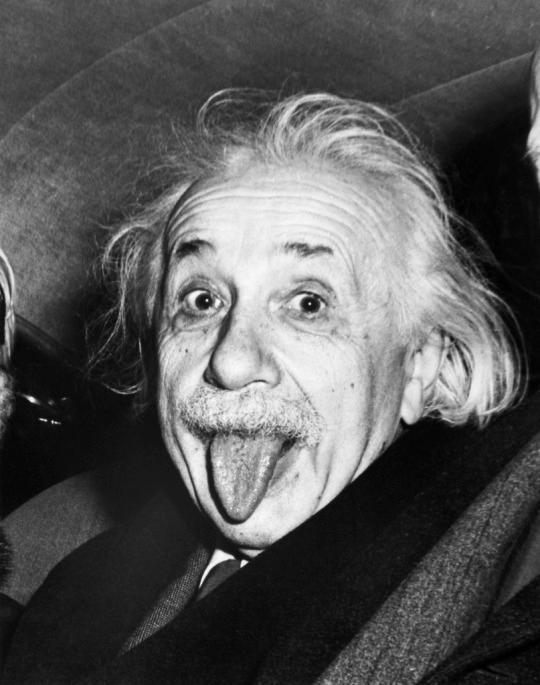

Most people tend to think of high IQ and genius as virtually the same, but they’re far from it. Albert Einstein’s estimated IQ is 160, but it was probably something else that gave him his special smartness sauce. Photo: Corbis/Arthur Sasse)

Einstein. Mozart. Socrates. Freud. Curie. Van Gogh. Newton. Locke. Jobs.

There’s intelligence, and then there’s genius. Everyone knows the famous names in history, of men and women who made game-changing contributions to their respective fields. But what is genius?

Earlier this week, Long Island high-school student Harold Ekeh earned acceptance into all eight Ivy League institutions, along with other respected universities like MIT and Johns Hopkins. He is, by all indications, a highly-intelligent young man. But will his name ever fall in alongside the greats?

Usually, we look at geniuses in retrospect, which makes cultivating and understanding genius a tall order. According to Richard Haier, Ph.D, a professor emeritus in the Pediatric Neurology Division of the School of Medicine at University of California, Irvine, the concept is not well understood.

“There are a lot of myths,” he tells Yahoo Health. “There’s a widespread belief that intelligence can be enhanced by enriching children’s lives early, but that has never been demonstrated by research. The research on genetic influences is stronger but how intelligence emerges as a child develops is not so clear, especially when we try to understand what genius is.”

This points to genetics, a major component in genius – but not the only one. Much of what we know to this point is blurry, yet developing and exciting. First, though, what is “genius” exactly?

More questions than answers

“There’s no one way to define genius,” Haier says. “For example, the high end of the IQ spectrum can be considered genius — say the top 0.1 percent of raw intelligence.”

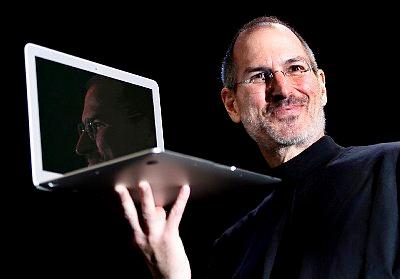

But that’s more or less intellect. Many smart people don’t accomplish much. Genius, we recognize, is something else. Haier goes further: “Does it take doing something great in your field?” he says. “Was Steve Jobs a genius? He certainly created products and a company that have changed the world. I have no problem calling him a creative genius, but was he always the smartest guy in the room in terms of IQ?”

Steve Jobs had a higher than average intelligence, but experts question if his intelligence was highly superior. (Photo: Corbis)

We don’t have an IQ score for the visionary behind Apple, although Walter Issaccson alludes that he may have taken the test. Very few will argue that he wasn’t a genius, though, regardless of whatever score he may or may not have gotten.

But would Jobs have become a genius without a counterpart? “Wozniak actually did the engineering,” says Haier. “The two were completely different in terms of personality and motivation. But in terms of creative engineering, he is a genius too. We know his name because of Apple, but there are many other similar geniuses who have created important things we use everyday but we don’t know their names. What it illustrates is there are different routes for people who are exceptional and get the label of genius.”

When it comes to defining genius, it’s a complex equation. “Can you be extremely creative and have average intelligence?” Haier asks. “There seems to be a threshold of at least above average intelligence for creativity, but not in all fields. Musical ability, for instance, may be more independent of intelligence. It’s very muddied – but you don’t need a precise definition to do scientific research. Over time, research increases the precision of the definition.”

The brain of a genius: is it bigger, better?

There’s some debate about the genius brain, and whether or not it’s superior than a brain of average intelligence. Research hasn’t given us a definitive answer on that yet. Earl Hunt, Ph.D, a professor of psychology and adjunct professor of computer science at the University of Washington, has studied individual differences in intelligence, and says genius is something else.

“Genius is an extremely rare event,” Hunt tells Yahoo Health. “I don’t think, biologically, they are very different, or that there is a ‘genius brain’ component to giftedness. You can have very bright people. I’ve personally known five Nobel laureates, and they’re smarter than me, but I didn’t think they were qualitatively smarter.”

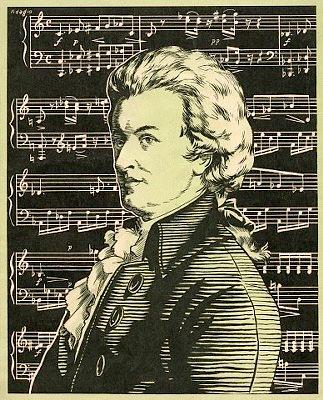

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is estimated to have an IQ of 165. But creative genius and intellect do not necessarily go hand in hand

Geniuses are certainly brilliant, though. So, if you peek inside the head of one of the best and brightest, is the brain any different than average? “It must be,” says Rex Jung, a neuroscientist, brain-imaging researcher and assistant professor of neurosurgery at the University of New Mexico. “Environment is going to be a huge contributor, but we bring to the table these genes that put us at the starting gate.”

Researchers are starting to see that every brain does not work the same way. Recent studies on structure have emerged that may explain why some people excel intellectually above their peers; a “smart brain” works in many ways, and men and women with the same IQ may have different architectures, with the pattern of white and gray matter informing a person’s specific strengths and weaknesses. However, this research is relatively early.

In terms of measuring superior intelligence in the day to day, test scores matter. “For anyone who thinks they don’t matter, there’s evidence to show they’re demonstratively wrong,” Haier explains. “Of course, there are outliers, but the scores are very predictive of academic success, which is predictive of life success.”

For instance, the Julian Stanley’s famous 1971 Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth has identified and followed 5,000 intellectually gifted men and women from before age 13. Now in their 50s, most have excelled considerably. Many of the men have gone onto successful STEM careers, and many of the women have become doctors, attorneys, and university deans and provosts.

Tests of cognitive ability (regardless of their content) evaluate a general factor of intelligence – otherwise known as a g factor. “The g factor is quite a good quantitative assessment,” Haier says. “Behavioral genetic studies show clearly that intelligence is highly heritable, but it looks like there may be hundreds of genes involved—each one contributing a small amount. It may be that geniuses have more of these genes than the rest of us, but we really don’t know yet.”

We also know that specific abilities within general intelligence matter, notably measures of verbal, quantitative and spatial reasoning. These can help predict where a bright person will excel most if they focus their skillset.

However, whether intelligence becomes genius is something else. “Cognitive abilities matter,” says David Lubinski, Ph.D, an expert on giftedness and a professor of psychology and human development at Vanderbilt University. “You can have a car with a big engine — but if there’s no gas in the tank, or the conditions are bad, you’re not going to go anywhere.”

The “secret sauce” of genius

Most people tend to think of high IQ and genius as virtually the same, but that’s a misnomer. “It’s a nice rubric for people to relate,” Jung says. “And if you’re smart, facile, quick, you’re going to be able to successfully solve problems 95 percent of the time.”

However, the ability to solve the rare problem is what separates smart from genius. “There are different networks in the brain that seem to engage in deductive reasoning, and those networks that are bigger, stronger and faster win the day most of the time,” Jung says. “Creativity, though, is the other network. It is slower, and allows for all the processes to run together. You’re figuring out how things might work with abstraction, metaphor.”

Jung calls creativity “the secret sauce” of genius, which leverages intelligence. “These two reasoning processes are highly adaptive, but the ability to think outside the box with creativity, through abductive reasoning, is key,” he explains.

Creativity allows for one to solve the problems that only arise infrequently – like resourcefulness in an earthquake, or figuring out how and why a personal relationship is going awry. It’s the interplay of intelligence and creativity that seems to inform genius; a person is able to solve a problem no one else is able to find a solution for, or see a societal need before it arises.

Creativity is somewhat linked to raw intelligence or IQ, according to Jung. “The correlation is about 0.3, but it tends to dissociate above 120, where they don’t seem as related — or even unrelated,” he says — which only gives rise to more questions about genius.

Cultivating genius not just about creativity, or intelligence, or both. Making valuable, lasting contributions to society is also about the right circumstances and personality traits.

Gender and personality matters

You could be the smartest person in the room, or on the continent, but you won’t excel without the proper internal and external tools. Facets of personality, according to Lubinski, play a major role in extreme giftedness.

“For example, 15 percent of the top one percent in intelligence don’t want to work 40-hour weeks,” he says. “Passion and motivation are important, and there are huge individual differences there. Exceptional achievers are always passionate about developing their talent.”

Motivation and dedication are huge factors playing into lasting success, although most discount them in favor of raw intelligence. “All the geniuses we know work very hard and prepare very hard,” says Hunt. “Einstein didn’t just dream up the theory of relativity. He was well-known for his grasp of late 19th century physics.” Ultimately, he spent years and years setting the table for his contributions.

Geniuses and highly-intelligent contributors also have to find their niche, and most do with the right motivation. Interestingly, men and women often play to different strengths. Lubinski says we see a unique distribution of men and women in various fields based on sex-specific traits.

“Men, relative to women, have more focused interests,” he says. “They want to hunker down in their caves and work on something, which is why we see a lot of them in STEM careers. Women, on the other hand, have flatter, more balanced interests. They excel in law and medicine — but not just any kind of law and medicine. They’re intellectual property lawyers, or surgeons training surgeons, or in administrative positions like university deans. They’re much more capable of thriving in these positions because they have more varied interests.”

Finding your niche is one thing, but in creating a genius, personality also matters. “Genius has a certain set of characteristics,” Jung explains. “Creativity is a big one, but there’s also persistence and obstinance. To break the mold, you have to keep pushing and pushing until someone tries your idea. And then there’s interacting with others, an openness — all of these are leveraging intelligence.”

Interaction is another component of genius. When we think of a genius, we tend to think of a singular person. However, there’s usually a supporting cast working alongside or behind the scenes of these men and women, allowing them opportunity to thrive.

The right circumstances

Intelligence and creativity mean very little without the right circumstances. Common threads include at least some means, hard work, a societal network and a supportive environment. “The supporting cast is extremely important,” says Hunt. “There’s this old saying, ‘You don’t ask Einstein to wash the dishes.’” Meaning, a genius is probably less likely to be bothered by everyday tasks, allowing him space to explore and create.

Hunt points to an American genius he knows, who he declined to name, but says has made major insights into his field. “As a 10- or 11-year-old, his family protected him,” he says. “He was off in the corner thinking. Geniuses are single-mindedly, extremely oriented toward their work.”

And close relatives, mentors and colleagues help encourage their work. For instance, Hunt mentions Sir Isaac Newton’s professor at Cambridge, who relinquished his position as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics in favor of his bright, young protege. The breaks have to go a bright person’s way.

You can be notably bright, but if you’re the time and place you’re born has everything to do with it. “The social setting has to be right,” Hunt says. “If you went deep into the Amazon and, lo and behold, found someone who had developed the wheel all on his own, would he be a genius? He was in the wrong society.”

If you trace geniuses back through the eras, you see a vivid cast of characters that were in contact and growing alongside, or just after, one another – and the ideas they were developing were in demand in each society. The Greeks, for instance, had an array of philosophers that are still relevant today, and intellectual thought was encouraged and supported.

Edinburgh in the late 17th and 18th century was populated with thinkers like Locke, Hume and Rousseau, who gathered together with colleagues and traded ideas. In the 18th and 19th century, composers like Mozart and Beethoven emerged to great acclaim from expectant audiences.

The historical venue was as important for major contributors’ work as their raw intelligence. “Having a society that valued and supported their ideas, giving them stable employment, made all the difference – having a core group to exchange ideas,” Hunt says. “The other advantage is that they were often first. The second to prove the Pythagorean Theorem won’t be considered that great a guy.”

To sum up, being smart isn’t everything. “I think most Americans vastly overrate personal quality,” Hunt says. “Most geniuses succeeded because everything fell just right.”

So what about Harold Ekeh, the Long Island high-school student who was accepted to all eight Ivies? Does he have a swimming chance?

Smarts, support, tenacity and luck might be the winningest predictive combination, but ultimately, genius is a developing mystery. “Brain power gets you in the race, but that’s all it gets you,” says Hunt. “We can measure the function, how fast they learn, individual differences in how the brain performs — but our ability to predict genius is really beyond anybody’s guess. Part of it is inspiration, part of it is perspiration.”

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(

Atom

)

No comments :

Post a Comment